Lou Costello, Hollywood’s best-loved comedian, tells how he fought his way back to health through prayer and undying faith.This an exclusive account to Motion Piture’s Readers

I think I’m a pretty lucky guy to be alive to tell this story.

With more than a half a year in bed spent grimly facing the terrifying prospect that I might never walk again, I found myself suddenly projected into a new world. A world that I never knew existed until then. And because I had never before come in contact with sickness and disaster, I suddenly saw a lot of things for the first time – things that before had meant very little to me.

Now that it is all over – and I’m told that it is – I think I’m very lucky to have made such rapid recovery from my illness. On March 6th I was stricken with rheumatic fever, that insidious and perplexing malady of which so little is known, and whose ravages, with a death toll equaling that of whooping cough, scarlet fever, measles and diphtheria combined, has become the Number One killer of the children of America.

All my life I have had a horror of dramatics, and I was glad that no one, that fateful day in March, told me that my days were numbered. I was glad that instead of shaking heads, and monosyllabic conversations, and whispered conferences behind closed doors, I was met on every side by smiling faces, cheering messages and corny jokes. More than anything else, this showed me that you can lick some of the worst with a little of the best that you friends have to give. And my friends certainly rallied around me.

It wasn’t easy, in those first, painful stages, to contemplate a future enclosed in four walls, bright as they were. It wasn’t easy to listen to a ball game over the radio, when you want to be sitting smack bang in the front row of the bleachers shouting your lungs out. And it wasn’t easy sometimes, knowing that everyone around you was able to do all the things that you yourself might never do again.

Yet, from the very beginning, I don’t think I ever quite contemplated the possibility of losing this battle, the weapons of which, unfortunately, are so few. Little to nothing is known of combating rheumatic fever successfully. Rest is the main solution, plus an open mind, the will to conquer and the stamina to take the bad with the good. I felt that I was capable of all that. But I don’t know I would have come out as well as I have without the strengthening influences of my friends, and the hundreds and hundreds of people who sent letters from all over the United States.

A particular tough day of pain, when contact of bedclothes with the infected limbs alone was almost beyond endurance, saw the arrival of batches of letters from children inflicted with the same discomfort, their pain, the sudden clouds on the horizon of their hopes must have been the same. Yet they all wrote with good humor, inspired evidences of indomitable spirit, and with that solid, simple faith in the future that is so wonderful in children. It wasn’t hard to reproduce in myself some of the content of those touching letters. You can’t stay in the sun and no feel a little of its warmth, of its magic healing qualities.

From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank again all those children, and their parents, and the hundreds of grown-ups, too, who sent in encouraging messages. I can’t say how happy it made me, and how much it has contributed towards my eventual, and I hope, final recovery.

It was on a Wednesday that I first felt the pains that were to send me to bed, and preclude activity on my part for over nine months. My whole life had been wrapped up in athletics. I was quite successful in the boxing arena, in the basketball game, and on the baseball field. I thought at first I was suffering from a “charley horse,” and that within a few hours it would clear up. On the following day it didn’t and I was trying vainly to remember how I might have overexerted myself. I resorted to hot and cold applications, and that evening on my usual broadcast I hopped about on one foot – the pain was so bad. The audience loved my antics, thinking it a new gag on my part. It was no gag, I assure you – although I couldn’t assure them.

The following day, Friday, there was no improvement in my condition and, because I was determined to go to the fights at the Hollywood Stadium, I spent the afternoon in bed to rest up for it. I got up to dress, and was walking across the room to pick up my clothes, when it happened. I stood still suddenly, rooted to the floor, and unable to budge an inch. This was a charley horse with a vengeance. The next day, Saturday, Dr. Victor Kovner told me that I had rheumatic fever. Hearing from him that it was a children’s disease reassured me; nothing, I thought that a child suffers can be serious.

The thing that hit me the most was the fact that I, who had never suffered a real sickness in my life, was now thoroughly incapacitated, with two useless sticks for limbs. It was quite a thought, what had happened to the pins that has seen me hitch-hike out here in 1926 to get a job as a laborer, one day a week, and netting me the weekly sum of $5. In those days I slept in cars on parking lots, on benches in squares, in partly-built houses, with nary a cold to stop me. I had hitch-hiked across the country in fifteen days, and those legs now couldn’t take me across the room. It hit pretty hard, I guess, when I looked back a little further, in to the world of home-runs, and ringed canvas, and being something of a basketball hero.

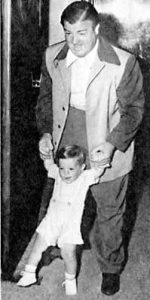

But the important thing now was to wait and see, and not look too much on the black side of things. It was while doing just this that I realized how much everything that was going on around me was quickly assembling itself in a pattern of peace and contentment and heartening encouragement. There was little Lou, Jr., the best hypo in the world with his gurgling laughter and struggle to say anything that sounded like a word. Carole Lou, 4 was neither very gay nor very puzzled at her father staying at home for so long; she took it in her stride, as I was trying to.

It was left to Patricia Ann, 7, to provide the only problem that I seemed to have. And that was to tell her the sick room of her Dad was hardly a playground, and that it wasn’t helping matters to have her leave it in a shambles after each of her visits. Behind my threats of suitable punishment Pat must have seen a lurking grin, because she would say, “Oh come now, Daddy, you know very well you can’t even get out of bed to do it!” Thus, when I got up for the first time, Patricia Ann sat on the floor at me quizzically, and said, “Things are going to be different from now on, aren’t they, Daddy?”

Not a day passed but Bud Abbott, my partner, didn’t make a loyal and lengthy appearance. Never, from him, so much as a remark as to what would happen to the team if anything happened to me. Throughout the nine months of my enforced rest I tried to get Bud to enjoy his long vacation by going away somewhere. Without even telling him I went so far as to buy plane tickets to Mexico City. But Bud sent them back, refusing to budge from his faithful daily routine of cheering me up with the best bedside banter. There was a heap of irony in this, too. All through our collective careers, Bud, the straight man, has never said any of the funny lines. Now all that was changed, and Dr. Kovner was just one of the few who admit that Bud’s new role had a lot to do with my getting well. He had received many offers to work alone, but he only laughed at them.

Another visitor was Joe Kirk, who entertains at The Bandbox, the little Valley night club that I once owned. From him the latest about the joint. Then Mitchell, our colored man, would drop in on matters pertaining to the house, as if I didn’t know that was a plot to keep me occupied, that everything had already been decided by Ann. But I can’t say I didn’t enjoy those interludes, or those of his wife, Ophelia, on matters relating to the kitchen. Many a hot dish was cooked up as a result of those conferences.

I remember, too, how I saw from my window that the trees behind the pool bore fruit, and how the lawn near the guest house needed something done to it, and whether my radio antenna wouldn’t be better moved over to the other side. I was a stranger looking at my own house. All of a sudden there were a million things to do. And I couldn’t help saying to myself, “Gosh, Lou, you’re not ill. You’re having a vacation. The first you’ve has in twelve years. Besides, you’ve got to get well; look at all the things around that need your attention.” As if they hadn’t done all the right without me. But it was all food for thought and, although I didn’t know it till now, it was just the food my illness needed: keeping my mind on everything but what ailed me.

Every night a movie was shown in my bedroom, and one of the most touching things that happened was that Clark Gable, whom I hardly know, and in the very midst of his war duties, took time out for one of his customary friendly gestures. Hearing of my sickness, he got in touch with his secretary and gave instructions that his entire library to 16 millimeter pictures were to be turned over for my use. I saw everything but Gone With the Wind, which was too expensive a production to be reproduced for home use, and I also saw all the wonderful pictures that lovely Carole Lombard made life bearable.

As for visitors, I never had enough of them, although the nurse would see to it that I didn’t overdo that. But I couldn’t do too much of it, not with people like Father Burdidge, of my parish, and the six nuns who came one after afternoon all together. Three of them had just returned from fourteen years’ missionary work in China and Japan, and three were leaving to take over the duties of the other three. They knew, as I did, that everything would come out all right. They were glad that I hadn’t neglected my prayers to God to get well.

Every mail brought new evidence of the friends I had. Prayers had been said for me in Jersey City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and I think that one of the things that touched me more than anything was that happened in New York. At a meeting there of the Stage Hands Union, a tough bunch of men at best, a halt was called to say prayers for my recovery.

Yes, throughout my six months in bed there were occasions for both tears and laughter. But the tears were of joy, for the friends I had made, and what they thought of me, and were doing for me.

I always got a laugh, but a grateful one, out of the letters of the well-meaning people who had the perfect cure for my ailment. One of them wanted me to bury an egg for three days in deep soil in the full light of the moon, and another wanted me to wear a boiled potato on the lapel of a pair of yellow pajamas. Others sent patent medicines, unbreakable walking sticks, and I even received a hanging strap with instructions to tie a copper wire from wall to wall, so that I could get about the room.

It was while I was spending me days at home that I thought of the hundreds of children who didn’t have the right kind of a place to recuperate in. I thought of all the children who had bleak, drab walls to stare at, and no view out of the window. I saw the question of neglected diets, incorrect medication; I saw a total lack of diversion or entertainment; I saw, most of all, their inability, because of impoverished circumstances, for complete rest.

That is why the Lou Costello Fund Foundation at 8511 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, is already in operation. My partner, Bud Abbott, and myself are glad that it will see eventually the building of a 200-bed sanatorium in the heart of Palm Springs for the treatment pure and simple of rheumatic fever. I hope, too, that it will only be the beginning and that the time will come when every child throughout the United States will have a place to go if stricken with the horrible plague.

My illness made me want to find out everything about rheumatic fever. We found out, among many things, that there are only 1,000 beds throughout the country for the treatment of rheumatic fever. It didn’t take me long to realize that out of this adventure of mind had come something of importance … the desire to give to others all the things which, thanks to my own circumstances and the love and care and loyalty of everyone around me, I was able to have. Under such conditions you can face almost anything. I want others to have the same chances to beat the rheumatic fever rap.

And I am attending to that little matter right now.

As we go to press, heartbreaking news just reached us.

On the evening of November 4, Lou Costello was scheduled to return to the air, It was to have been a gala occasion, celebrating his miraculous recovery from rheumatic fever which has bedded him for nine long months. Thousands of loyal Costello fans were listening eagerly all over the country for the incomparable little man who had brought them so many laughs and so many moments of merriment.

A few hours before broadcast time, it was the sad task of Lou’s doctor to tell him that his youngest child, Lou, Jr., whom Lou mentions so tenderly in the above story, had been drowned in the family swimming pool. The child would have been a year old the following Saturday, and a gay birthday party had been planned for the little boy. Only that morning Lou had carefully chosen a teddy bear as his birthday gift to his son.

The news of the tragedy so stunned the comedian that his doctor feared a collapse. But with the help of Bud Abbott, he pulled himself together and, following the tradition of the theater, insisted that he go on with the show.

Lou Costello went on the air that night. He laughed, he yelled, and gags flowed. Mickey Rooney stood by throughout the entire show to take over if he should falter or miss a cue. But not until the last gag had been delivered did the little comedian sink into a chair. Not until then did the tears, so sternly withheld, began to flow down his cheeks. Not until then did the listening audience learn of the tragedy, when Bud Abbott stepped up to the microphone and made a simple announcement.

Our deepest sympathy goes to a wonderful man, one of the greatest troupers the theater has ever known.

(originally published in Motion Picture Hollywood Magazine, January , 1944)